Flowing through the Ranger uranium mine lease and into Kakadu National Park, Magela Creek is home to important populations of native fish species that need to be able to move between the river, floodplain and escarpment country at different times of the year.

Weathering of waste rock from the mine releases contaminants, including magnesium sulfate, a salt. These contaminants are washed out by the rain and are predicted to move through the local groundwater towards Magela Creek. Depending on the concentration, the magnesium sulfate has the potential to affect fish, trees and other freshwater ecosystems in and near Magela Creek downstream from the Ranger mine site.

There were two main parts of the project.

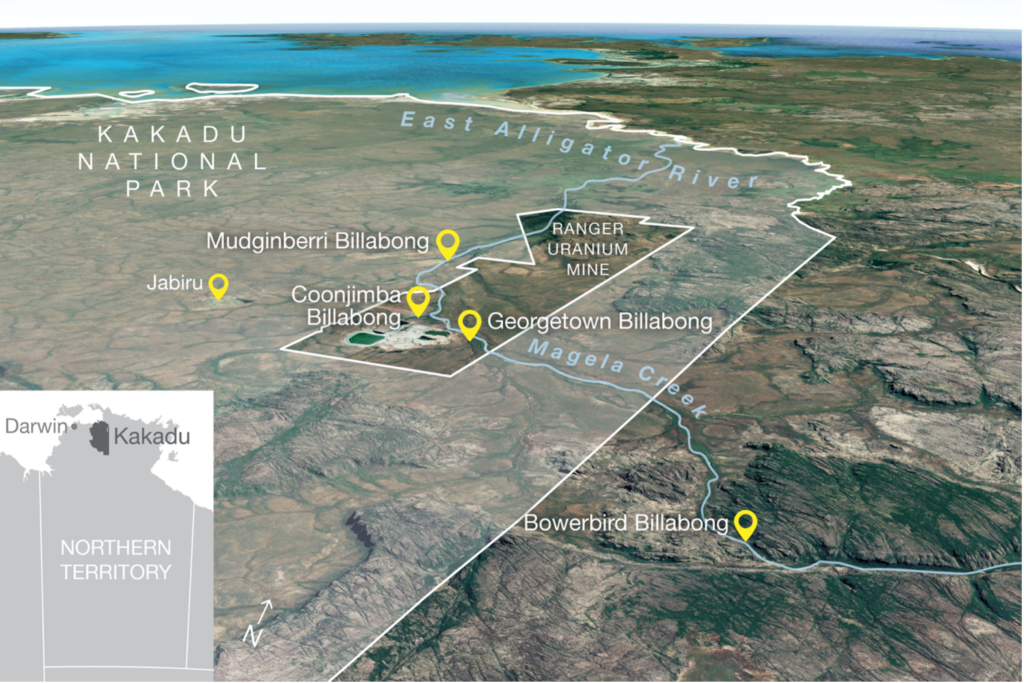

Location of Kakadu National Park, Magela Creek, Ranger uranium mine and the four billabongs where fish were collected, tagged and detected.

The Northern Australia Environmental Resources Hub addressed key research questions to come up with practical, on-ground solutions to some of the north’s most complex environmental challenges. A transdisciplinary research approach has been at the heart of the hub. Integrating key research users – policy-makers and land managers including Traditional Owners and ranger groups – into the co-design of research projects has led to rapid uptake of research outcomes into land management practices and decision-making. The hub has produced this wrap-up video outlining these impacts from the perspectives of research users.

Hub research in NT’s Magela Creek is increasing our understanding of whether fish in the freshwater creek move differently in the presence of salty mine wastewater.

This project is being led by Associate Professor David Crook from Charles Darwin University (CDU). A/Prof Crook is being assisted by researchers from CDU and the Supervising Scientist Branch of the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment.

This project is due for completion in June 2021.

Contact

David Crook, Charles Darwin University

david.crook@cdu.edu.au